Across the Pond and the Northern Frontier

While British English and Canadian English share strong historical ties due to colonization, their evolution has resulted in significant differences. Influenced by both British and American English, Canadian English forms a unique middle ground, with distinctive variations in vocabulary, pronunciation, spelling, and even cultural expressions. Whether you’re a student, traveler, or language enthusiast, understanding these distinctions enhances communication between these two varieties of English.

Vocabulary: A Blend of British and American Terms

In Canada, many words align with British English, but there are some notable differences. Canadian English also borrows elements from American English, creating a blend of both vocabularies. Let’s look at a few examples:

- British: flat (apartment) /flæt/

Canadian: apartment /əˈpɑːtmənt/

(Canadians, like Americans, use “apartment” instead of “flat.”) - British: biscuit (cookie) /ˈbɪskɪt/

Canadian: cookie /ˈkʊki/

(Though “biscuit” exists in Canada, “cookie” is more common, aligning with American English.) - British: jumper (sweater) /ˈʤʌmpə/

Canadian: sweater /ˈswɛtə/

(In Canada, “jumper” usually refers to a sleeveless dress worn over a shirt, while “sweater” is used for warm tops.)

Spelling: British Influence Prevails

Despite its proximity to the United States, Canadian English retains many British spellings.

- British: colour /ˈkʌlə/

Canadian: colour /ˈkʌlə/

(Like British English, Canadian English uses “-our” spellings for words like colour and favour.) - British: realise /ˈrɪəlaɪz/

Canadian: realize /ˈrɪəlaɪz/

(For verbs, Canadian English often follows the American “-ize” pattern instead of British “-ise.”) - British: theatre /ˈθiːətə/

Canadian: theatre /ˈθiːətə/

(Canada retains the British “-re” endings for words like theatre and centre.)

Pronunciation: Subtle Differences with British Roots

Canadian English pronunciation differs from British English, particularly in vowel sounds, but shares similarities with American English. Some distinct Canadian pronunciation features include:

- Canadian Raising: In Canadian English, certain diphthongs are pronounced with a raised first part of the vowel. For example:

- British: about /əˈbaʊt/

Canadian: about /əˈbəʊt/

(In Canada, the “ou” sound in words like about is pronounced with a raised vowel, sounding almost like “a-boat” to British ears.)

- British: about /əˈbaʊt/

- British: schedule /ˈʃɛdjuːl/

Canadian: schedule /ˈskɛdjuːl/

(Canada follows the American pronunciation of “schedule”, starting with a hard “sk” sound, instead of the British “sh” sound.)

Grammar: Similar Structures with a Few Tweaks

In terms of grammar, Canadian English is quite similar to British English, but it borrows elements from American English as well. One noticeable difference is in the use of collective nouns:

- British: “The team are playing well.”

Canadian: “The team is playing well.”

(Canadian English tends to follow the American approach of treating collective nouns as singular, while British English often treats them as plural.)

Another minor variation is how Canadians handle prepositions. For example, they might use “on the weekend” (like Americans), whereas British English prefers “at the weekend”.

- British: “I’ll see you at the weekend.”

Canadian: “I’ll see you on the weekend.”

Cultural Context: British Influence Meets North American Pragmatism

Though Canada retains a deep connection to British traditions, especially in formal settings, its language reflects the influence of its North American neighbors. Canadian English is a reflection of Canada’s diverse cultural history, blending British, American, French, and Indigenous influences. For example, in some regions, particularly Quebec, Canadian English is sprinkled with French loanwords. Additionally, Canadian politeness is often reflected in their speech patterns, making frequent use of the word “sorry.”

Practical Examples in Context

Let’s compare how a conversation might differ between British and Canadian English:

British:

- A: “I’ll park the car in the car park before heading to the flat.”

- B: “Don’t forget to grab some biscuits for tea!”

Canadian:

- A: “I’ll park the car in the parking lot before heading to the apartment.”

- B: “Don’t forget to grab some cookies for coffee!”

Common Mistakes Learners Make

One common mistake for learners of Canadian English is assuming it’s simply a mix of British and American English. While it does borrow elements from both, Canadian English has its own unique quirks, such as Canadian raising and the British preference for “-our” spellings. Additionally, learners might confuse “sorry” as a filler word, which Canadians use more frequently than either British or American speakers.

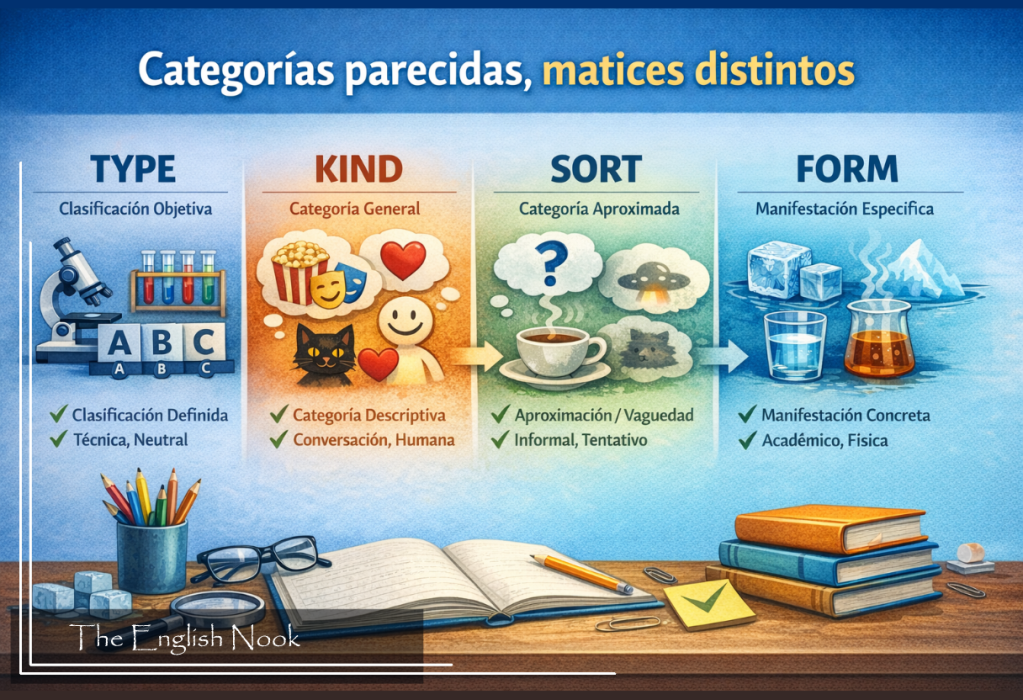

Visual Comparison Chart

| Feature | British English | Canadian English |

|---|---|---|

| Vocab | Flat, Biscuit, Jumper | Apartment, Cookie, Sweater |

| Pronunciation | /əˈbaʊt/ for “about” | /əˈbəʊt/ for “about” |

| Spelling | Colour, Realise, Theatre | Colour, Realize, Theatre |

| Grammar | The team are playing well. | The team is playing well. |

Straddling the Line Between British and American English

Canadian English occupies a unique space, maintaining a blend of British and American linguistic features while developing its own identity. Its differences in vocabulary, pronunciation, spelling, and grammar are essential for effective communication, especially for students and travelers. Learning these distinctions allows you to navigate the nuances of both British and Canadian English more confidently.

Mastering Canadian English means embracing a hybrid language that blends the best of British and American English, all while adding its own northern charm!

Read part two here:

Differences Between British and Canadian English: A Closer Look – Part 2

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a reply to waydaws Cancel reply