Knowing a Word Is Not a Yes-or-No Question

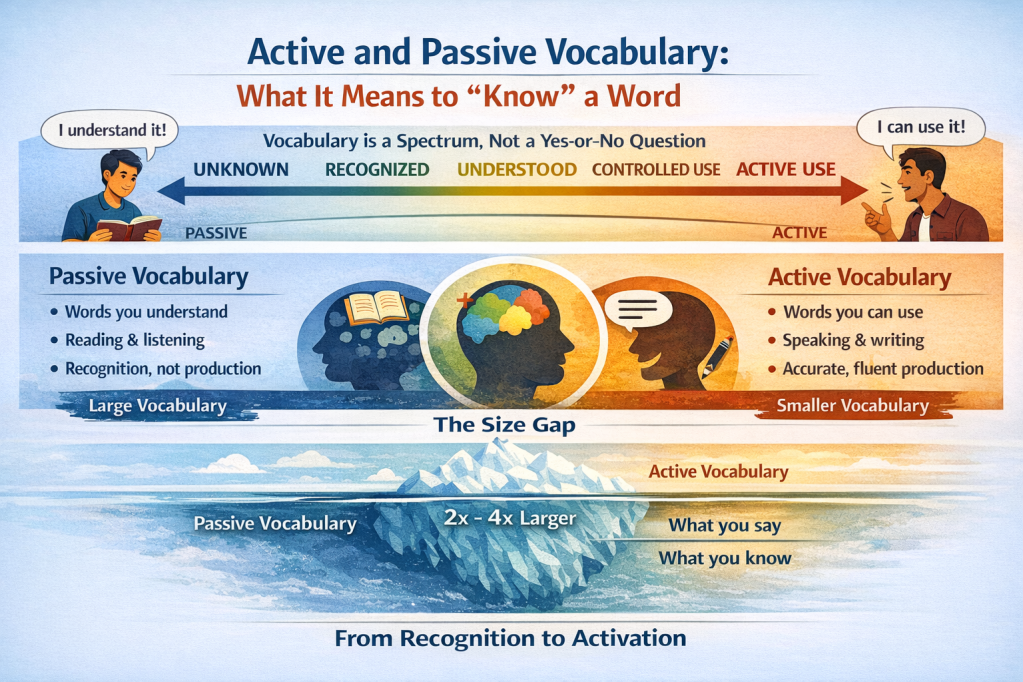

When people talk about vocabulary size, they often assume a simple definition: a word is either known or unknown. In reality, vocabulary knowledge exists on a spectrum. You may recognize a word instantly when reading, hesitate before using it in speech, or avoid it altogether despite understanding it perfectly.

This is where the distinction between active (productive) and passive (receptive) vocabulary becomes essential. Understanding this difference not only clarifies why language learning can feel uneven, but also explains why learners often “know” far more than they can actually say.

What Is Passive Vocabulary?

Passive vocabulary consists of words you can recognize and understand when you encounter them, but which you do not reliably produce yourself.

You typically access passive vocabulary when:

- reading a text

- listening to someone speak

- hearing a word in context

You may understand the meaning clearly, but:

- you hesitate to use the word

- you are unsure of its exact form or collocations

- it does not come to mind spontaneously

Passive vocabulary grows rapidly because it is fueled by exposure. Every book, film, conversation, or article adds to it. Importantly, passive knowledge requires less cognitive effort than active use.

What Is Active Vocabulary?

Active vocabulary includes the words you can produce accurately and appropriately in speaking or writing.

A word is active if you can:

- recall it without prompting

- pronounce or spell it correctly

- use it in a grammatically and contextually appropriate way

Active vocabulary is what enables fluent communication. It is smaller, slower to build, and far more demanding cognitively. Activating a word requires retrieval, confidence, and control — not just recognition.

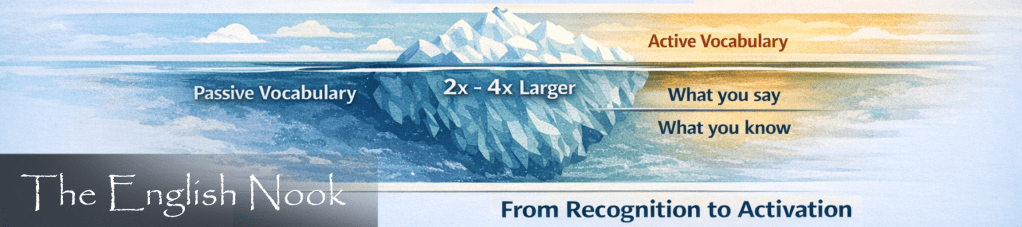

The Size Gap: Why Passive Vocabulary Is Always Larger

For almost all speakers, including native speakers, passive vocabulary is significantly larger than active vocabulary.

Typical ratios for second-language learners:

- Passive vocabulary: 2–4× larger than active

- At advanced levels, the gap can be even wider

This imbalance is not a failure; it is a natural consequence of how the brain handles language. Understanding a word requires recognizing meaning, but using it requires selecting it, forming it correctly, and deploying it under real-time pressure.

Vocabulary Is a Continuum, Not Two Boxes

It is tempting to think of active and passive vocabulary as two separate lists, but in reality words move gradually along a continuum:

- Unknown – never encountered

- Recognized – looks or sounds familiar

- Understood – meaning is clear in context

- Controlled use – can be used with effort

- Automatic use – fully active

Most vocabulary sits somewhere in the middle. Many words remain permanently passive, and that is entirely normal — even desirable. A rich passive vocabulary supports comprehension and learning, even if not every word becomes active.

Why Passive Vocabulary Is Not “Useless”

Passive vocabulary often gets undervalued, but it plays a crucial role in language development.

A strong passive vocabulary:

- improves reading and listening comprehension

- accelerates the learning of new words

- provides raw material for future activation

- reduces cognitive load during communication

In fact, active vocabulary almost always grows out of passive vocabulary. Words are rarely activated without first being understood repeatedly in context.

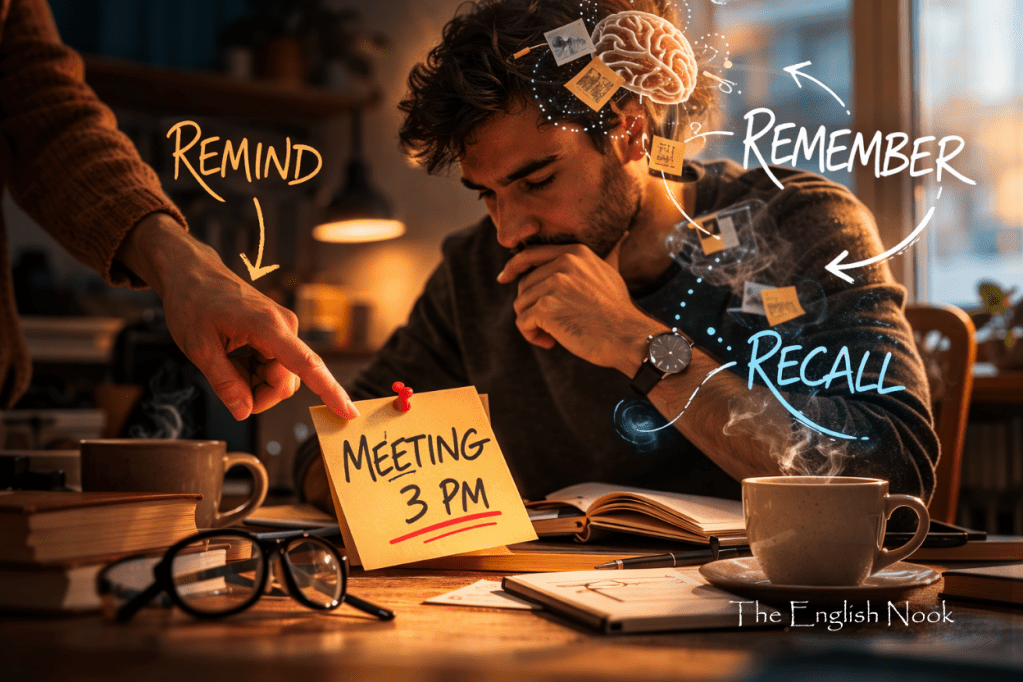

Why Activating Words Is So Difficult

Moving a word from passive to active requires more than time. It requires:

- repeated retrieval (not just recognition)

- use in varied contexts

- production under slight difficulty or pressure

This is why learners may understand complex texts but struggle to speak fluently. Comprehension tolerates ambiguity; production does not.

Active vocabulary demands precision.

Implications for Language Learning and Teaching

This distinction has direct consequences for how vocabulary should be learned:

- You can encounter many words passively in a lesson or text

- You should target far fewer words for active mastery

Trying to activate too many words at once often leads to frustration and shallow learning. Effective lessons usually:

- select a small core of words for active use

- surround them with a larger passive vocabulary environment

This explains why recommendations such as 10–20 new words per lesson make sense only when referring to active vocabulary targets, not total exposure.

A Common Misunderstanding

When learners say:

“I learned 40 new words today”

They usually mean:

“I recognized or understood 40 new words.”

That is not a problem — but it is not the same as adding 40 words to active use. Confusing these two types of knowledge often leads to unrealistic expectations and unnecessary discouragement.

Fluency Is About Activation, Not Accumulation

Language learning is not about collecting words like items in a list. It is about building layers of access to vocabulary, from recognition to confident use.

Passive vocabulary provides breadth.

Active vocabulary provides power.

Progress happens not when you expose yourself to more words, but when you systematically activate the words you already understand.

So a useful final question to ask yourself is:

Are you spending more time adding new words —

or giving existing words the chance to become active?

Both matter. But fluency lives in the second.

Fluency begins where recognition becomes action.

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a comment