The Privatization of English Learning: How a Global Skill Became a Global Commodity

In an increasingly interconnected world, proficiency in English has transformed from a valuable asset into a near-essential requirement for social mobility, academic advancement, and economic opportunity. However, behind the banner of “global communication” lies a powerful and often overlooked reality: English learning has become a privatized, profit-driven industry. This shift has turned language education into a commodity, one that deepens inequality and reshapes the global landscape of opportunity.

A Billion-Dollar Industry Built on Aspirations

The global English-teaching market is now worth tens of billions of dollars, sustained by language academies, standardized tests, private tutors, online platforms, and multinational publishing houses. English is no longer just a language—it is a business model.

Companies market it as the passport to a better future, promising career growth, international travel, and academic prestige. For many families, investing in English is framed not as enrichment but as necessity—a form of “linguistic insurance.”

This commercialization means that access to high-quality English instruction depends heavily on socioeconomic status. Those who can afford private lessons, exam preparation courses, or elite bilingual schools gain a decisive advantage, while those who rely solely on underfunded public schools fall behind. In many countries, the cost of learning English has become a symbolic entry fee to the global economy.

Gatekeeping Through Certification

Another layer of privatization is embedded in standardized tests such as IELTS, TOEFL, Cambridge English, and other globally recognized certificates. These exams have become gatekeepers for university admissions, work visas, and even residency permits.

While positioned as objective measurements of proficiency, they come with high financial barriers: exam fees, preparatory materials, coaching academies, and retake costs. For individuals from low-income backgrounds, even a single attempt can be prohibitively expensive. As a result, English certification becomes not just a test of ability, but a test of financial means.

This creates a paradox: the very tool promoted as a pathway out of poverty often requires economic privilege to access in the first place.

The Unequal Geography of English

Privatized English learning also reinforces urban-rural divides. Major cities host premium language centers staffed with experienced instructors, while rural areas may lack qualified teachers, stable internet, or adequate materials.

Even within cities, affluent neighborhoods attract well-funded academies and international schools, while lower-income districts rely on overcrowded classrooms and outdated resources.

This geographic inequality shapes life trajectories. A student in a wealthy urban district may begin English immersion at age three; another in a rural community might not encounter consistent English instruction until adolescence. By adulthood, the gap has widened into a structural divide that impacts employability and income.

English as a Market—Not a Right

The privatization of English learning raises a deeper ethical question: should proficiency in the world’s dominant language be treated as a market commodity, or as a fundamental educational right?

When English becomes a product sold to the highest bidder, it stops being a tool for global communication and becomes a mechanism of exclusion.

People are not merely judged on their ability to express ideas, but on their ability to afford the linguistic capital demanded by employers and institutions.

This is particularly problematic because the benefits of English are not distributed equally. Multinational companies require English even in countries where daily operations do not involve English-speaking partners. Universities demand high test scores even for programs taught in local languages. International job platforms filter candidates based on English rather than actual job-relevant skills.

In this system, English proficiency does not simply reflect educational background—it reinforces and reproduces existing social hierarchies.

Psychological and Cultural Consequences

Beyond economics, the privatization of English learning influences identity and self-worth.

Learners from disadvantaged backgrounds may internalize the idea that their “non-standard” accents or imperfect grammar reflect lower intelligence or professionalism—not because of actual incompetence, but because the industry implicitly equates linguistic prestige with human value.

This can lead to linguistic insecurity, anxiety, and even shame about one’s native language—an emotional cost rarely acknowledged in discussions about global communication.

Toward a More Equitable Model

Addressing these imbalances does not require rejecting English; instead, it requires rethinking how access to English is distributed. Governments and institutions can implement policies that counteract privatization:

- strengthening English programs in public education,

- subsidizing exam fees for low-income learners,

- investing in teacher training and community-based instruction,

- expanding multilingual resources,

- and recognizing alternative methods of competence assessment.

Technology also offers potential if deployed responsibly. AI-powered learning tools can democratize access—provided they support multiple languages, remain affordable, and avoid reinforcing biases.

Ultimately, the goal should be to transform English from a market commodity into a shared resource—one that empowers learners without marginalizing those who lack economic privilege.

The Cost of a Global Language

The privatization of English learning reveals a paradox at the heart of globalization: the language that promises connection often creates division.

As long as high-quality instruction remains locked behind paywalls and standardized tests function as financial barriers, English will continue to widen the gap between those who can afford opportunity and those who cannot.

A more equitable future is possible—but only if English is treated not as a luxury, but as a public good.

Language should open doors, not sell them.

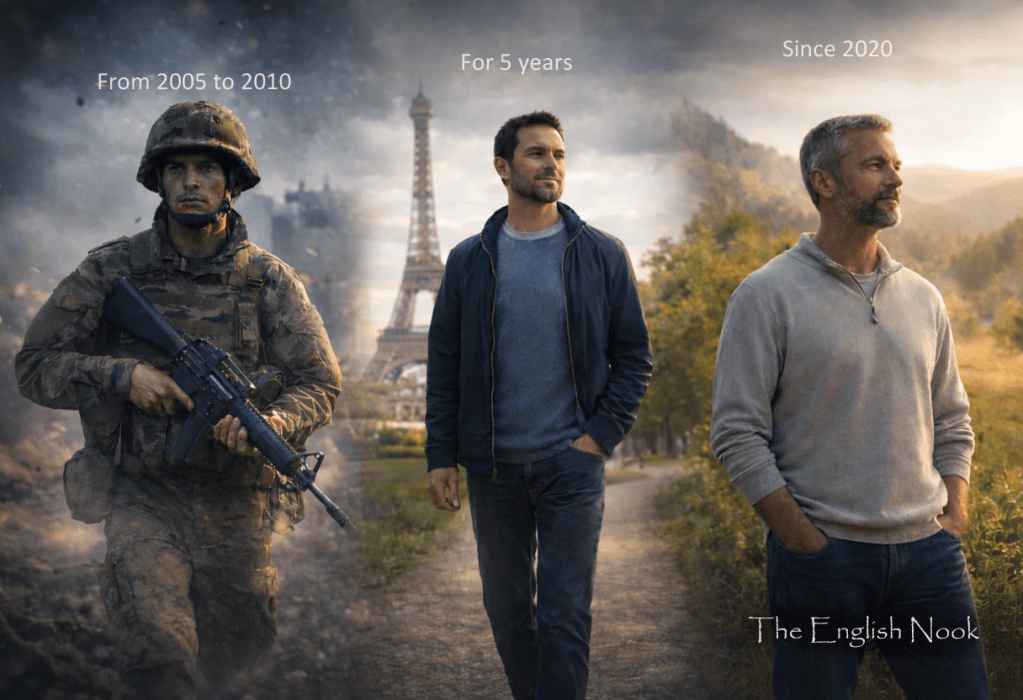

And this is exactly why, at The English Nook, we are committed to making learning resources accessible to everyone.

If English is truly meant to connect the world, its tools should never be reserved for the privileged few.

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a comment