Whispers After the Laughter

When the laughter fades and the candles inside jack-o’-lanterns sputter out, the morning of November 1st dawns quietly. The world exhales after Halloween’s carnival of masks and mischief. Yet beneath that silence lies a story older and deeper than the costumes we wear or the candy we trade — a story of faith, fear, and the power of words.

This day, known as All Saints’ Day, has not only shaped centuries of tradition but also left a subtle imprint on the English language itself. Behind every whisper of Halloween echoes a prayer once spoken in Latin, chanted in Old English, and carried forward into modern speech.

From Pagan Fires to Sacred Bells: The Origins of All Saints’ Day

Long before English existed, early European peoples marked the turning of autumn with festivals of harvest and remembrance. The Celts celebrated Samhain, believing that on the last night of October, the boundary between the living and the dead grew thin. When Christianity spread across the British Isles, the Church sought not to erase such customs but to transform them. The feast of All Saints’ Day — or All Hallows’ Day — was established to honor every saint, named and unnamed, and to redirect the energy of older rites toward sanctity.

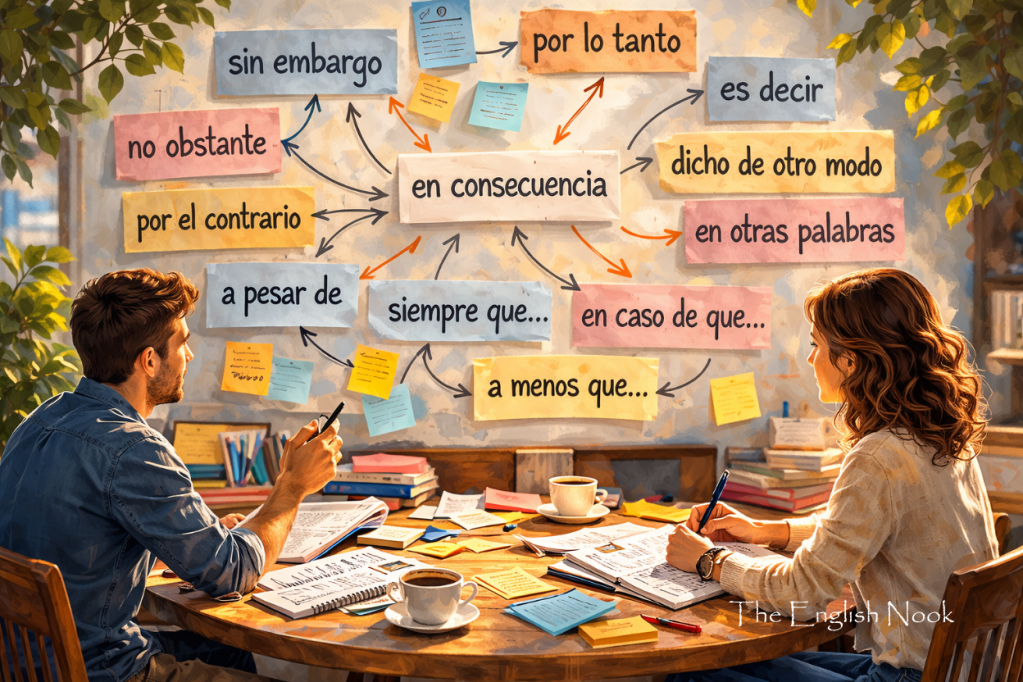

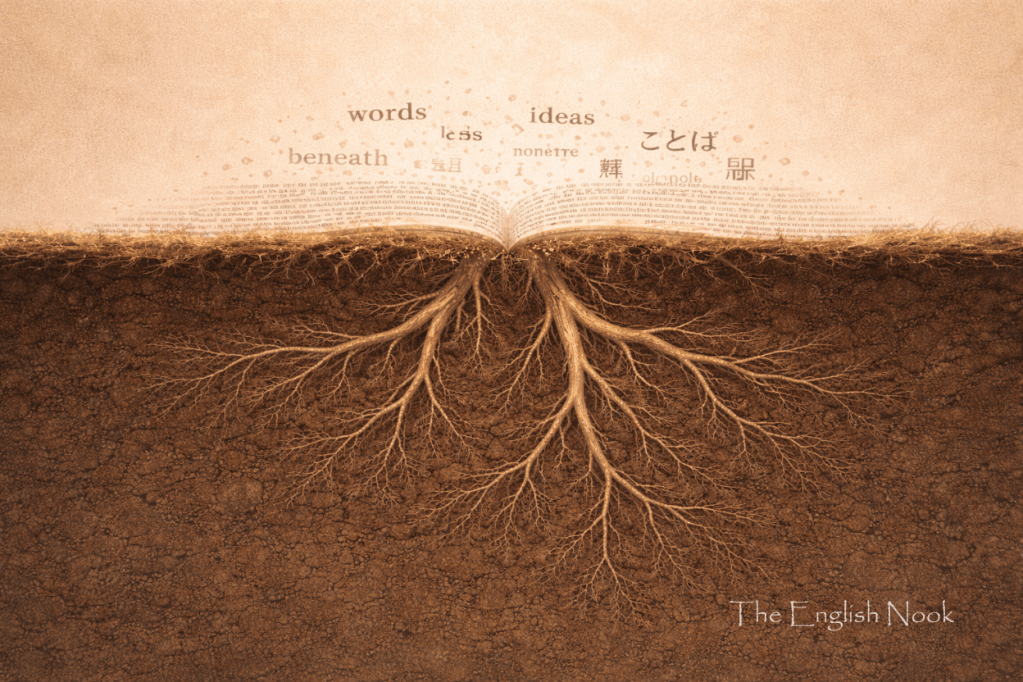

In this blending of pagan and Christian worlds, the English tongue found fertile ground. It absorbed Latin, Old Norse, and Celtic echoes — and from this mixture came one of its most mysterious and enduring words: Halloween.

From Hallows to Halloween: The Birth of a Word

The very existence of the word Halloween depends on All Saints’ Day.

In Old English, hallow meant holy person, derived from halga, a term connected to halig, meaning holy. The feast day was thus All Hallows’ Day, and the night before it — All Hallows’ Eve. Over centuries, the phrase contracted: Hallowe’en, and eventually, Halloween.

Each syllable of the word carries history — a linguistic palimpsest showing how faith, ritual, and sound shift over time. By the Middle Ages, “hallow” had largely yielded to saint in everyday speech, yet the Church calendar preserved it, ensuring its survival through annual repetition. Every time the English spoke of All Hallows’, they kept a fragment of their linguistic ancestry alive.

Lingering Words: Sacred Echoes in English

Though many medieval words vanished, hallow lingered in sacred and poetic language. It appears in the Lord’s Prayer — “Hallowed be thy name” — and in Shakespeare’s lines about “this hallowed time.” In later centuries, the word came to describe anything revered: hallowed halls, hallowed ground, hallowed traditions.

Its endurance reflects more than theology; it reveals how language sanctifies memory. Even phrases like “no saint” or “to make a saint of someone” trace their roots to this vocabulary of holiness. Through idiom and metaphor, English preserved not only religious concepts but also the moral imagination that accompanied them.

Language is a mirror of belief. The persistence of hallow reminds us that the sacred has never fully left English speech — it simply hides in familiar words, waiting to be recognized.

The Cultural Bridge: Between Darkness and Light

If Halloween belongs to the shadows, All Saints’ Day belongs to the dawn. Together, they form a cultural bridge — a movement from fear to faith, from playfulness to reverence. This duality captivated generations of English writers.

In Robert Burns’s “Halloween” (1785), rustic revelry mingles with hints of the supernatural. Christina Rossetti’s devotional poems, meanwhile, turn the focus toward purity and salvation on All Saints’ Day. The juxtaposition reveals a distinctly English fascination with thresholds — between night and morning, mortal and divine, terror and transcendence.

Even in modern literature and film, the echo remains. Ghost stories end with reflection; horror gives way to mourning or renewal. The rhythm established by Halloween and All Saints’ Day — the shiver, then the stillness — continues to shape how English-speaking cultures tell stories about death, memory, and what may lie beyond.

A Quiet Legacy in Modern Times

Today, All Saints’ Day passes almost unnoticed in much of the English-speaking world, overshadowed by Halloween’s glittering spectacle. Yet its influence endures quietly. It gave us a word that unites sacred and secular tradition. It preserved ancient vocabulary. And it taught the language to balance levity with solemnity — to turn fear into reflection.

The fading of All Hallows’ Day from popular culture mirrors a broader transformation: the shift from ritual to entertainment, from commemoration to consumption. But English, ever adaptive, remembers. In every hallowed hall, every Halloween, every saintly metaphor, the old meaning glows faintly beneath modern speech.

Where Language Remembers the Sacred

November 1st is more than the morning after a night of costumes and candy. It is a linguistic and cultural hinge — a moment when the English tongue recalls its own layered past. Halloween could not exist without All Saints’ Day; the word of revelry was born from the word of reverence.

In this way, the language itself embodies the human condition: half shadow, half light. We celebrate fear, yet we long for faith. We tell stories of ghosts, yet we whisper prayers for souls. And so English — ever the witness of centuries — carries within it both the thrill of the dark and the sanctity of dawn.

Perhaps that is the quiet message of the day after Halloween: that beneath every mask, every story, every word we speak, there still lingers the echo of something hallowed.

When laughter dies, language remembers — beneath every “Halloween,” something hallowed still whispers.

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a comment