From Many Tongues to One:

The Latinization of Hispania

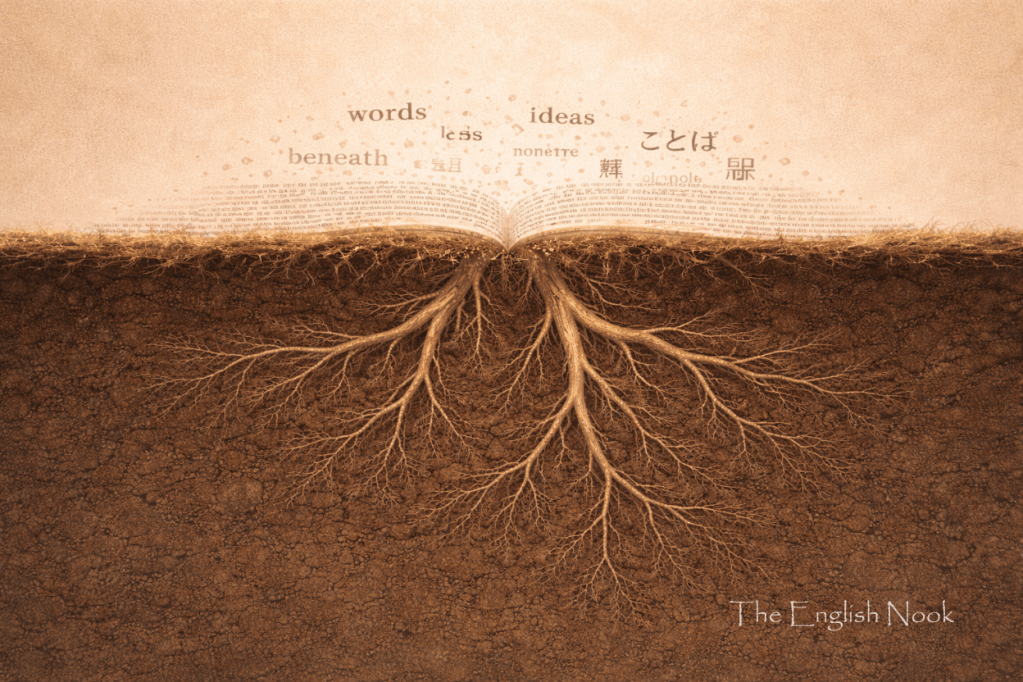

The evolution of Spanish and its Romance dialects cannot be understood without first looking back to the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, a transformative process that lasted from 218 BCE to 19 BCE. This conquest was not simply a political or military campaign—it marked the beginning of a profound cultural and linguistic unification under Rome.

Before Latin became dominant, Hispania was a mosaic of peoples and languages, each with its own character and legacy:

- Celtiberian

A branch of the Celtic languages, Celtiberian was spoken across the central plateau (modern-day Soria, Zaragoza, Teruel). It was written using an adapted Iberian script and shows a fascinating blend of Celtic grammar with Iberian influences. Words like segisama (“victory”) and tribal names such as the Arevaci and Belli survive in inscriptions. Celtiberian contributed agricultural and everyday vocabulary to the Latin spoken in these regions, leaving a subtle trace in later Romance. - Lusitanian

Found in western Hispania (roughly modern Portugal and western Spain), Lusitanian remains somewhat mysterious. Scholars debate whether it was Celtic or pre-Celtic, since its inscriptions share features with both. Place names like Lusitania (the Roman name for Portugal) and words tied to religion and the natural world show its distinct identity. Some Iberian Romance words—such as carro (“cart”)—may reflect Lusitanian roots. - Iberian

Spoken along the Mediterranean coast (Catalonia, Valencia, and southeastern Spain), Iberian was a non-Indo-European language unrelated to Latin or Celtic. It had its own scripts (the Iberian alphabets) and appears on coins, stelae, and ceramics. Although we can read the Iberian script, the language itself is still not fully understood. Place names such as Saguntum (modern Sagunto) preserve its memory. Some Iberian phonetic patterns may have subtly influenced the way Latin was adopted in eastern Hispania. - Tartessian

Possibly the earliest attested written language of the peninsula (dating from the 8th–6th centuries BCE), Tartessian was spoken in the southwest, in what is now Andalusia and Extremadura. It was written in an early semi-syllabic script. Scholars still debate whether it was Celtic or pre-Celtic, but it represents a bridge between indigenous Iberian languages and later Celtic arrivals. While Tartessian as a language disappeared, the region’s contact with Phoenicians and Greeks enriched its lexicon and culture before Latin arrived. - Basque (Euskera)

The great exception is Basque, a language isolate with no known relatives. Unlike Celtiberian, Lusitanian, Iberian, or Tartessian, Basque survived Romanization and continues to be spoken today in northern Spain and southwestern France. Its survival owes much to the geographical protection of the Pyrenees and the resilience of its speakers. Basque also influenced Latinized speech in the area: many linguists suggest that the loss of the initial Latin “f-” in Spanish (ferrum → hierro) reflects the influence of Basque phonology, which lacked the /f/ sound.

The Impact of Latinization

This extraordinary linguistic diversity made Hispania a cultural crossroads. The Phoenicians had brought their alphabet, the Greeks their colonies, and the Carthaginians their influence, but no one before the Romans had imposed a unifying language across the entire peninsula. With Rome’s arrival, Latin became the common tongue of law, trade, and military command, gradually absorbing or replacing the local idioms.

Crucially, however, the Latin that spread was Vulgar Latin—the everyday, flexible form spoken by soldiers, settlers, merchants, and farmers—not the polished, literary Latin of Cicero or Virgil. This is the Latin that gave rise to Spanish, Galician, Catalan, and other Romance dialects.

How Latin Spread Across Hispania

The spread of Latin was not uniform. Several factors shaped its adoption:

- Urban vs. Rural Divide

Cities such as Tarraco (Tarragona), Emerita Augusta (Mérida), and Corduba (Córdoba) became strongholds of Latin because they housed Roman settlers, administrators, and trade networks. In contrast, rural areas often retained local speech for longer, creating pockets of linguistic resistance.- Example: In urban Córdoba, Latin inscriptions from the 1st century CE show rapid adoption of Roman culture and language.

- In the mountainous northern regions (Cantabria, the Basque Country, Asturias), indigenous languages and Celtic traditions lingered much longer.

- Geography and Isolation

The mountain ranges of Iberia—such as the Pyrenees and Cantabrian Mountains—prevented linguistic uniformity. Isolated valleys preserved distinct ways of speaking Latin, sowing the seeds for future dialectal divergence.- Example: Latin spoken in the northwestern corner (Galicia) developed unique traits, laying the foundation for Galician-Portuguese.

- Military and Colonization

Roman soldiers and settlers brought Latin into every corner of Hispania. Veterans were often granted land in conquered territories, becoming agents of Latinization. Latin became a marker of Roman identity and social mobility: to advance in the army, politics, or trade, one had to speak it.

From Classical Latin to Vulgar Latin

It is important to highlight that Vulgar Latin differed in pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary from Classical Latin. Over time, the differences widened. Examples illustrate this transition:

- Classical Latin → Vulgar Latin → Future Romance Forms

- equus (“horse”) → caballus (common term in Vulgar Latin, meaning “workhorse”) → caballo (Spanish), cavallo (Italian).

- lupus (“wolf”) → lupu (simplified Vulgar form) → lobo (Spanish), loup (French).

- oculus (“eye”) → oclu → ojo (Spanish), occhio (Italian).

These shifts demonstrate how spoken Latin simplified word endings, reduced consonant clusters, and preferred more “popular” synonyms.

The Role of Substrate Languages

Latinization did not erase local languages overnight; instead, elements of them survived as substrates, subtly influencing the Latin spoken in Iberia.

- Celtiberian & Lusitanian contributed vocabulary related to the natural world:

- camisa (“shirt”) may come from a Celtic root.

- carro (“cart, wagon”) also traces back to Celtic.

- Iberian influenced toponyms (place names), many of which survive:

- Sagunto, Ilerda (modern Lleida), Ilipa.

- Basque had a lasting phonological impact. Many scholars argue that features like the loss of initial /f/ to /h/ in Spanish (Latin ferrum → Spanish hierro) may be due to Basque influence, since Euskera lacks the /f/ sound.

The Fragmentation of Latin

By the 5th century CE, the Western Roman Empire was collapsing under political instability, economic decline, and barbarian invasions. Without centralized control and education, Latin in Hispania began to fragment regionally.

- In Galicia and northern Portugal, Latin developed differently than in Castile or Aragón, giving rise to Galician-Portuguese.

- In the eastern Pyrenees, contact with southern France influenced the emergence of Catalan.

- In Castile, the variety of Latin evolved toward what would become Castilian Spanish, absorbing Basque and Arabic influences later.

By this point, Latin in Hispania was no longer one uniform tongue but a family of developing dialects, which would evolve into the Iberian Romance languages.

Example of Regional Divergence

Let’s take the Latin word lacte (“milk”):

- In Castilian: leche (with the /kt/ cluster simplified to /ʧ/).

- In Catalan: llet.

- In Galician/Portuguese: leite.

This simple word reflects how the same Vulgar Latin base fractured into distinct Romance outcomes, depending on region.

Seeds of Diversity

The Latinization of the Iberian Peninsula was both a unifying and fragmenting process. While Latin imposed a common cultural framework, the geography, local languages, and uneven Romanization ensured that it evolved differently across regions. By the end of Roman rule, Hispania was already linguistically diverse, with the first cracks of what would become Spanish, Galician, Catalan, and other Romance dialects.

From Rome to Romance: how one empire’s tongue became many voices.

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

Need some help with your Spanish journey? Go to the contact area and send me a message; I’ll get back to you as soon as possible!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE:

Leave a comment