🔹 Introduction 🗣️

When learning a new language, pronunciation often presents one of the greatest challenges. Even learners with strong grammar and vocabulary may struggle to sound natural or be understood clearly. One major reason for this is phonological interference—the influence of a learner’s first language (L1) on their production of second language (L2) sounds.

This phenomenon involves more than just accent. It can result in consistent errors that alter meaning, affect fluency, or cause miscommunication. Understanding the types and causes of phonological interference can help learners, teachers, and linguists address pronunciation issues more effectively.

🔸 What Is Phonological Interference?

Phonological interference occurs when learners transfer the sound rules (phonology) of their native language into their second language. Because the brain is wired to use familiar speech patterns, learners unconsciously rely on their L1 when attempting to produce unfamiliar L2 sounds.

For example, a native Spanish speaker might pronounce “ship” and “sheep” the same way, because Spanish doesn’t differentiate between /ɪ/ and /iː/. Similarly, a French speaker may drop the English /h/ sound altogether, saying “house” as “ouse,” since /h/ doesn’t exist as a phoneme in French.

This interference affects:

- Individual sounds (consonants and vowels)

- Stress patterns

- Rhythm and intonation

- Syllable structure

🔸 Types of Phonological Interference

1. Substitution

Learners substitute unfamiliar sounds from the L2 with the closest equivalent in their native language. This happens when the L1 lacks the phoneme present in the L2.

🔹 Example:

- Japanese speakers may confuse /r/ and /l/, since Japanese has a liquid sound that falls somewhere between the two.

- “Rice” may sound like “Lice”, or vice versa.

- Spanish speakers often substitute the English /v/ with /b/, resulting in:

- “Very” → “Berry”

✅ Tip: Practice minimal pairs (like “light/right” or “vest/best”) and use visual aids like the IPA chart to highlight differences.

2. Omission

Learners omit sounds that do not exist in their L1 or that are difficult to produce due to L1 constraints.

🔹 Example:

- French speakers often omit the /h/ in words like “happy” or “hotel”, producing:

- “appy” instead of “happy”

- Mandarin speakers, whose language rarely ends in consonants, might say:

- “bike” → “bi”

- “map” → “ma”

✅ Tip: Draw attention to commonly omitted sounds and use slow, exaggerated pronunciation for practice.

3. Insertion (Epenthesis)

Some learners insert vowels or consonants to “fix” clusters that don’t exist in their L1. This typically happens with complex consonant clusters at the beginning or end of English words.

🔹 Example:

- Spanish speakers often insert a vowel before an initial /s/ + consonant cluster:

- “school” → “eschool”

- “stop” → “estop”

- Korean speakers might insert a vowel between consonants:

- “spring” → “seu-pu-ring”

✅ Tip: Practice common consonant clusters in isolation, then in full words. Use hand gestures or visuals to show the cluster structure.

4. Stress Pattern Interference

Each language has rules about which syllables are stressed, and this can interfere with L2 word and sentence stress. Misplacing stress may not always hinder communication, but it can sound unnatural or emphasize the wrong part of a word.

🔹 Example:

- In Spanish, stress often falls on the penultimate syllable, while in English, stress is unpredictable.

- “REcord” (noun) may be pronounced “reCORD” (verb stress) by mistake.

- French speakers, whose native language has fixed final-syllable stress, may stress the wrong syllable in English multisyllabic words.

✅ Tip: Use rhythm drills, stress marking, and stress-timed poetry or songs to build natural patterns.

5. Rhythm and Intonation Interference

Languages differ in rhythm types:

- Syllable-timed languages (like Spanish, French) give equal time to each syllable.

- Stress-timed languages (like English, German) reduce unstressed syllables and lengthen stressed ones.

When L1 rhythm is applied to L2, it can make speech sound robotic, rushed, or unnatural.

🔹 Example:

- A Spanish speaker might pronounce each syllable in “comfortable” evenly, as “com-for-ta-ble”, rather than blending to say “COMF-tuh-bl”.

- A Mandarin speaker might use flat or rising tones in English, leading to unnatural intonation that sounds like a question when it’s not.

✅ Tip: Encourage mimicry of native speech through shadowing, use of audiobooks, or acting out dialogues with proper prosody.

🧭 Why Understanding This Matters

- Communication Efficiency

Even small pronunciation shifts can change meaning:

- “Beach” vs. “bitch”

- “Sheet” vs. “shit”

- Confidence Building

Learners who improve pronunciation often feel more fluent and capable, even if their grammar stays the same. - Better Listening Skills

Phonological awareness doesn’t only help speaking—it helps learners hear and recognize new sounds better.

✅ How to Overcome Phonological Interference

| Strategy | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Pair Practice | Focus on pairs like ship/sheep, bet/bat | Practice listening, repeating, and distinguishing |

| Recording & Playback | Self-awareness through comparing own voice with native models | Use phone apps or recording software |

| Shadowing | Repeat after audio tracks in real time | Speeches, TED Talks, movie dialogues |

| Use of IPA and Mouth Diagrams | Teach how sounds are produced physically | Compare tongue/mouth positions between L1 and L2 |

| Targeted Pronunciation Drills | Focus on known interference patterns | Ex: /r/ vs. /l/ for Japanese learners, /th/ for most non-native speakers |

🔚 Conclusion

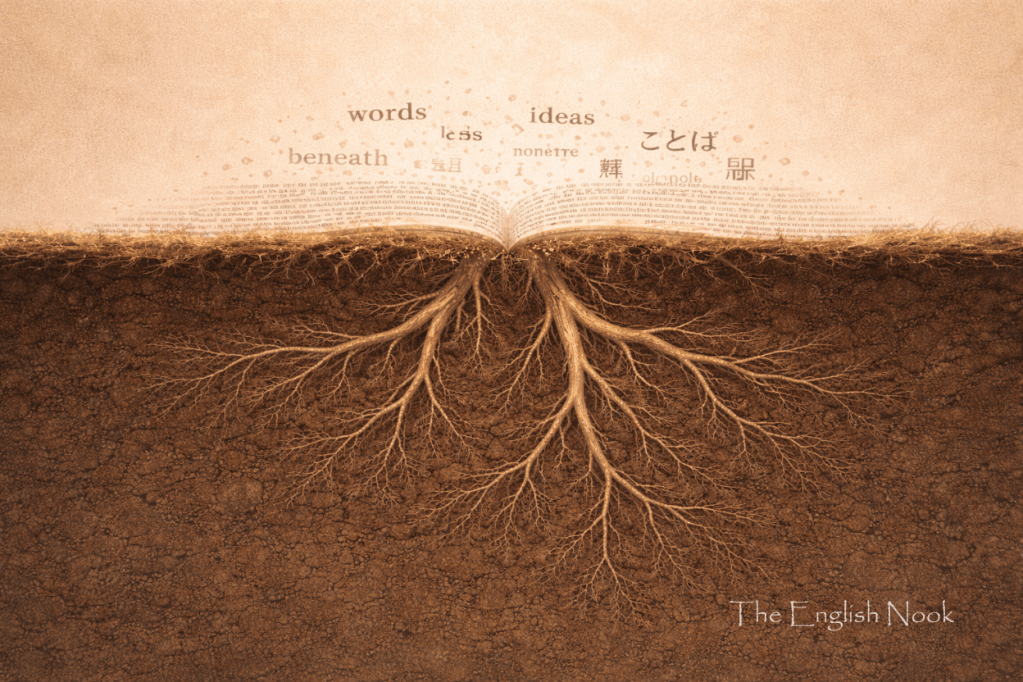

Phonological interference is a natural part of second language learning. It’s not a flaw—it’s a clue. It reveals where the learner’s brain is leaning on familiar patterns to manage unfamiliar sounds. While some interference is harmless and even gives learners an accent, others can lead to confusion or loss of meaning.

By identifying and addressing common types of interference—substitution, omission, insertion, stress, and rhythm—learners can make remarkable progress in pronunciation. With the right tools, awareness, and practice, phonological interference can be reduced, and clearer, more confident communication can emerge.

Your native tongue whispers—don’t let it trip your speech.

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a comment