🧠 The Blended Stage

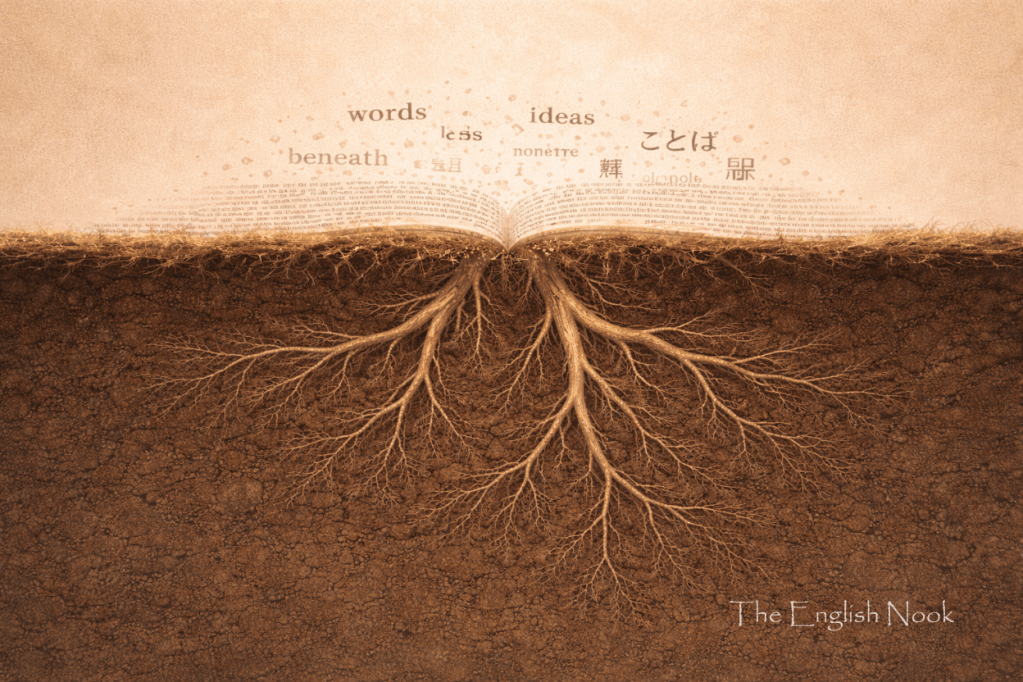

Learning a new language is more than just absorbing grammar rules and vocabulary lists—it’s a creative, mental process. Along the way, most learners pass through a fascinating stage known as interlanguage.

Interlanguage is not just a confused mix of two languages. It’s a unique, evolving system your brain constructs as it moves toward fluency. Understanding this stage helps you see that even your “mistakes” are meaningful—and necessary.

🔍 What Is Interlanguage?

Interlanguage is the transitional mental grammar that language learners build as they move from their native language to the target language. It’s not quite the first language, and not yet the second—it’s something in between.

Think of it as a bridge your brain constructs to cross from what you know to what you’re trying to learn. It borrows from both sides:

- 🗣 Your native language (L1)

- 📘 The target language (L2)

- 🤔 Your own internal logic and generalizations

This system is:

- Flexible – it changes with experience

- Rule-based – but often based on personal or guessed rules

- Unique – each learner has their own version

So, if you’ve ever said something like “He goed to school”, that’s not failure—it’s your interlanguage showing its work.

⚙️ How Interlanguage Develops

As you learn a new language, your brain is constantly experimenting. It:

- Applies patterns from your native language

- Makes logical guesses based on limited input

- Generalizes grammar rules

- Adjusts based on correction and exposure

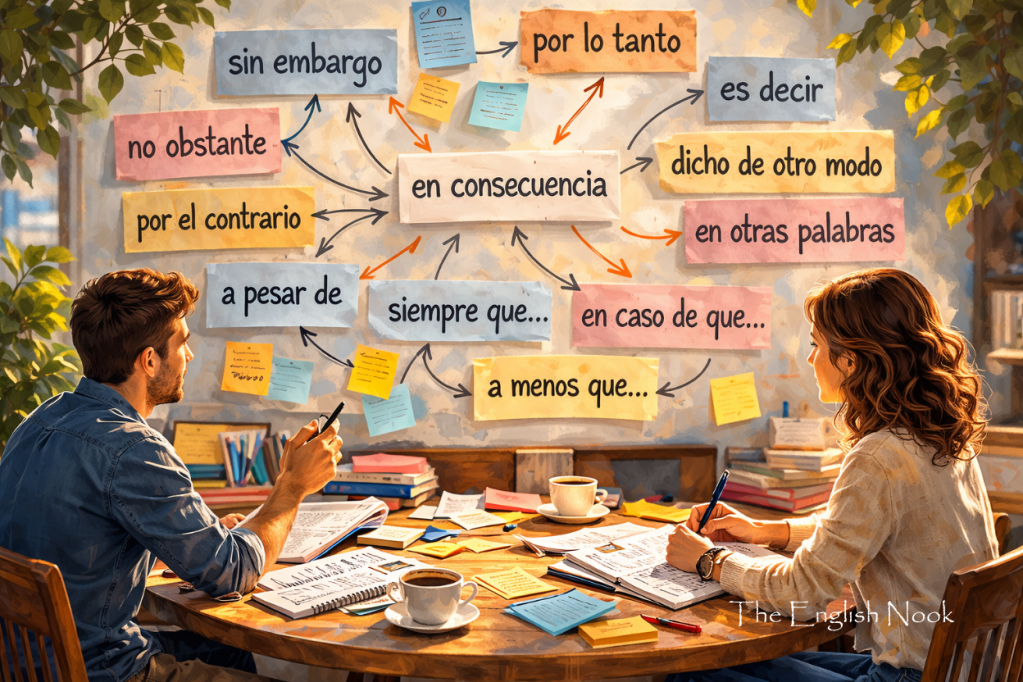

This leads to patterns like:

- Overgeneralization

“He eated breakfast.”

→ Applying regular past tense rules to irregular verbs. - Simplification

“She go store now.”

→ Leaving out auxiliaries or articles to reduce complexity. - Hybrid forms

“I have 25 years”

→ A direct translation from Spanish “Tengo 25 años” instead of “I am 25.”

These aren’t random errors—they reflect how your internal system is evolving.

🔄 Interlanguage vs. Interference

Many confuse interlanguage with interference, but they’re different concepts:

| Interlanguage | Interference (Negative Transfer) |

|---|---|

| A learner’s evolving internal grammar | Errors caused by influence from a known language |

| Reflects guesses and experimentation | Reflects unconscious transfer of native patterns |

| Natural and unavoidable in all learners | More common when languages share features |

| Can include unique forms | Usually mirrors L1 structures inappropriately |

👉 Example:

- Interlanguage: “I goed home.” – based on a guessed rule.

- Interference: “I have 25 years.” – translated directly from L1.

Both occur during language learning, but interlanguage is broader and often includes interference as part of the process.

🧊 Fossilization: When Interlanguage Gets Stuck

Sometimes, parts of your interlanguage stop evolving. This is called fossilization—when certain errors become fixed, even after years of use.

For example:

- A learner always says “She don’t like it” instead of “She doesn’t like it”, despite repeated correction.

Fossilization often happens when:

- The speaker can communicate effectively despite the errors

- There’s little corrective feedback

- Motivation to improve has decreased

- The environment reinforces the incorrect form (e.g., other learners make the same error)

The good news? Fossilization isn’t permanent. With awareness, feedback, and intentional practice, you can reshape even long-standing habits.

🛠 How to Work With Your Interlanguage

Rather than trying to eliminate interlanguage, use it as a tool to improve. Here’s how:

1. Notice Patterns

Pay attention to your recurring errors. Are they logic-based? Influenced by your native language?

2. Get Feedback

Work with teachers or native speakers who can gently correct mistakes and explain why.

3. Compare Languages

Study grammar and vocabulary contrastively. Knowing the differences helps you understand your tendencies.

4. Keep a Language Journal

Track your common mistakes and what you think causes them. Reflection turns confusion into insight.

5. Embrace Mistakes

Every error reveals how your internal system works—and how it’s improving. Your brain is actively testing hypotheses.

💬 Final Thoughts

Interlanguage isn’t a problem—it’s proof that your mind is doing the complex work of building a new language system. Like scaffolding on a building, it’s there to support your growth. Yes, it may look messy. Yes, you’ll make mistakes. But every step is part of the structure.

So when you catch yourself saying “She go yesterday” or “I am agree”, don’t be frustrated. Smile. You’re learning. And your brain is doing something remarkable.

Interlanguage: Where your mistakes aren’t wrong—they’re the roadmap to fluency.

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a comment