Beyond the Basics

In Part 1, we explored key differences between British and American English in vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar, and spelling. However, these variations go beyond simple word swaps and accent shifts. Dialects, idiomatic expressions, speech patterns, and cultural influences further distinguish these two major English varieties. In this second part, we’ll delve into regional dialects, idiomatic expressions, intonation, and the impact of media, highlighting how English continues to evolve on both sides of the Atlantic.

Regional Dialects: A Country Within a Country

Just as British English encompasses multiple dialects (e.g., Cockney, Scouse, Geordie), American English is not monolithic. Here are some key American dialects and their notable traits:

- Southern English (Southern U.S.): Features a distinct drawl, dropping of “g” in words ending in -ing, and unique expressions such as “y’all” (you all) and “fixin’ to” (about to do something). Double modals like “might could” (meaning “might be able to”) are also common, and vocabulary includes terms like “buggy” (shopping cart) and “coke” (used generically for any soft drink).

- New York English: Known for the pronunciation of “coffee” as /kɔɪfi/ and dropping of “r” in some words (e.g., “car” sounds like “cah”). New Yorkers also use unique expressions like “on line” instead of “in line” when waiting in a queue.

- Midwestern English: Considered the most neutral American accent, often used in news broadcasting. Features the “caught/cot” merger, where both words sound the same. Common Midwestern phrases include “pop” (for soda) and “ope” (an exclamation used when bumping into someone or making a mistake).

- African American Vernacular English (AAVE): A distinct linguistic system with unique grammar (e.g., habitual “be” in “He be working” to indicate a recurring action) and vocabulary influences. AAVE has contributed many expressions to mainstream English, such as “lit” (exciting), “woke” (socially aware), and “finna” (about to).

- Appalachian English: Retains archaic words and phrases, such as “afeared” (afraid) and “reckon” (think). Other distinct features include “holler” (small valley), “britches” (trousers), and “sigogglin’” (crooked or uneven).

In contrast, British dialects show vast diversity as well. Received Pronunciation (RP) is often associated with formal or traditional British speech, but regional variations like Scouse (Liverpool), Brummie (Birmingham), Cockney (London), and Geordie (Newcastle) have distinct phonetic identities and vocabulary. For example, Scouse features a unique nasal intonation and words like “la” (friend), while Cockney is known for rhyming slang, such as “apples and pears” (stairs). Brummie has a flatter intonation, and Geordie includes words like “bairn” (child) and “canny” (good or nice). Each of these dialects carries a deep connection to local identity and history, making British English incredibly varied depending on the region.

Idiomatic Expressions: The Heart of Everyday Speech

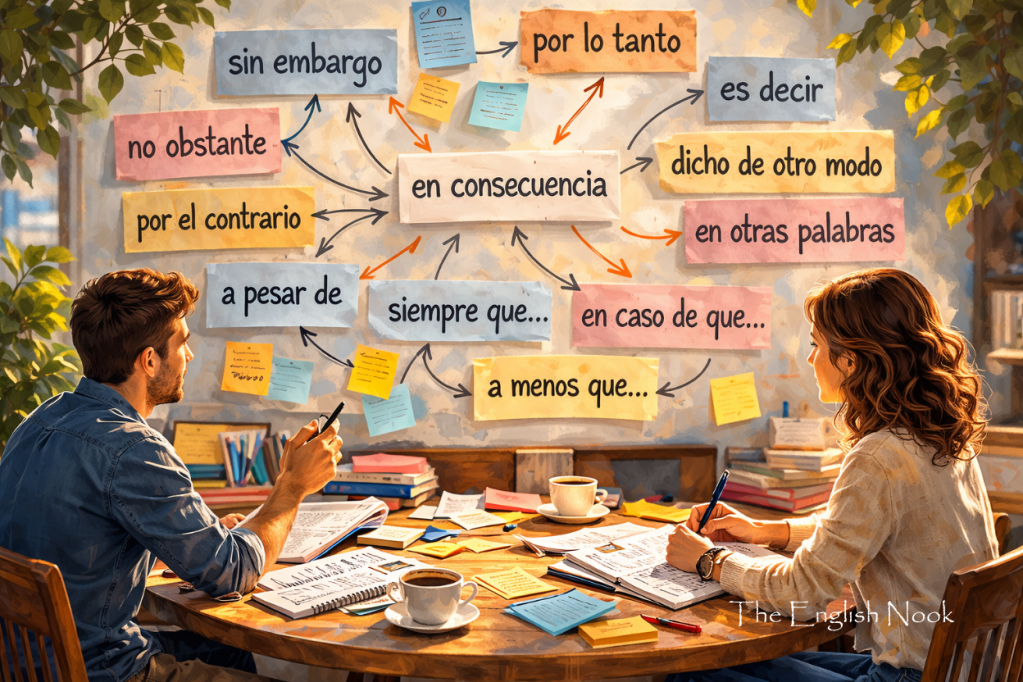

Idioms and phrasal verbs add personality to English, but many are unique to their respective regions. Here are a few notable examples, with equivalent expressions where possible:

- British Idioms:

- “Bob’s your uncle” – It’s as simple as that. (American equivalent: “Piece of cake”)

- “Taking the mickey” – Teasing or mocking someone. (American equivalent: “Pulling someone’s leg”)

- “Throw a spanner in the works” – Cause a problem or obstacle. (American equivalent: “Throw a wrench in the works”)

- American Idioms:

- “Hit the sack” – Go to sleep. (British equivalent: “Hit the hay”)

- “Shoot the breeze” – Chat casually. (British equivalent: “Have a chinwag”)

- “Jump the gun” – Act too soon. (British equivalent: “Beat someone to the punch”)

Phrasal verbs also differ. For instance, Brits tend to say “fill in a form,” while Americans say “fill out a form.” Similarly, British speakers might “write to someone,” while Americans simply “write someone.” In Britain, you might “call round to see a friend” (visit them), whereas in the U.S., you’d “stop by.” Brits tend to “knock off work” (finish work for the day), while Americans “get off work.” These variations can lead to misunderstandings if learners aren’t familiar with both versions, as the same verb combinations can have different meanings or not be used at all in the other variety.

Intonation and Stress Patterns: More Than Just Pronunciation

Apart from accent differences, intonation patterns distinguish British and American speech. Here are a few key contrasts:

- Rising vs. Falling Intonation: American English often has a more consistent rising-falling pattern in statements, whereas British English sometimes uses a rising intonation at the end of declarative sentences, making them sound more questioning.

- Syllable Stress Differences: Certain words are stressed differently:

- British: advertisement /ˌædvəˈtaɪzmənt/

- American: advertisement /ˈædvərˌtaɪzmənt/

- British: controversy /ˈkɒntrəvɜːsi/

- American: controversy /kənˈtrɑːvɚsi/

Such differences affect how speakers perceive tone and intent in conversation.

The Role of Media in Language Evolution

With globalization, media has become a key player in shaping language. While American English dominates films, TV, and digital culture, British English retains influence in literature, academia, and global business. Some notable trends include:

- Hollywood & Pop Culture: American slang spreads rapidly through movies, TV shows, and music (e.g., “cool,” “awesome,” “dude”).

- British Literature & Prestige: British English often appears in formal education and literary works, maintaining its association with traditional English language learning.

- Internet & Social Media: The rise of informal writing on social platforms blends elements of both dialects, with younger generations adopting a mix of British and American terms.

Why Understanding These Differences Matters

Recognizing these deeper distinctions between British and American English is crucial for effective communication, whether in professional, academic, or social contexts. Beyond mere vocabulary swaps, these variations reflect cultural identities and regional histories, enriching the way we engage with the English language.

By mastering both varieties, learners can navigate different English-speaking environments with confidence, appreciating the richness and adaptability of the language. And remember—whether you say “cheers” or “have a good one,” both versions of English are equally valid, just shaped by their unique histories and cultural landscapes.

Same language, different worlds—mind the gap!

If you’ve read everything, please consider leaving a like, sharing, commenting, or all three!

YOU WILL ALSO LIKE READING:

Leave a comment